Why Period Dialogue Sounds Like a Modern Fantasy

Most “period dialogue” isn’t historical speech—it’s modern language wearing a costume to stay emotionally legible. Everyday talk in many pre-modern contexts was more instrumental: coordination, status, obligation, and survival rather than self-explanation.

Posted by

Related reading

Choosing India Over the US Visa Path

Moving back to India wasn’t forced by visa trouble or failure—it was a deliberate trade for fairness, workable healthcare, and personal agency. The post breaks down why the hidden costs of the US immigrant “stability” story didn’t feel worth it.

When Burnout Makes You Root Against Your Own Principles

The author notices an uncomfortable relief when people they once defended are denied bail—not from changing beliefs, but from exhaustion with camp politics and outrage culture. The piece argues for separating civil liberties from tribal loyalty, practicing proportionality, and living without a camp.

“Just ask” is often treated as the safest, most polite move—but every question imposes an attention and responsibility cost on someone else. A better norm is self-resolution first, and asking only when the cost of being wrong exceeds the cost of interrupting another mind.

Period movies don’t sound like the past. They sound like what we want the past to sound like.

Most “period dialogue” isn’t a reconstruction. It’s a translation layer: modern speech with a dusting of old words, delivered in a tone that signals history.

And it makes sense. Real historical speech—especially everyday speech—would land wrong to modern ears. Not “wrong” as in immoral or stupid. Wrong as in: anticlimactic, repetitive, blunt, and often strangely procedural. If filmmakers tried to be linguistically accurate, many audiences would feel emotionally locked out. The characters wouldn’t sound heroic. They wouldn’t sound “written.” They would sound busy.

That’s the tradeoff almost every period film makes: believability over accuracy.

Everyday speech wasn’t a performance. It was coordination.

Modern dialogue (in movies and in life) assumes speech is where we do our inner life. We name feelings, negotiate identities, justify ourselves, and offer verbal reassurance. A lot of our social belonging is built out of that.

In many pre-modern contexts, speech had a different job:

- coordinate work

- transmit obligations

- mark status

- exchange news

- enforce norms

- negotiate resources

Not because people didn’t have emotions. Because language wasn’t treated as a constant emotional interface. You could feel deeply and still speak sparsely. Often, the feeling was expected to be obvious from the situation.

That’s why “realistic” historical dialogue can feel flat. It doesn’t narrate itself.

Here’s the texture of it—short, practical, almost administrative:

- “The wheat is thin.”

“How thin?”

“Half.”

“Then we eat less.”

Or a marriage conversation that doesn’t look like romance or tragedy, just logistics:

- “You marry him tomorrow.”

“I don’t know him.”

“You will.”

“Will he beat me?”

“Only if he’s drunk.”

Even when something huge happens, speech can stay narrow. Not because it didn’t matter—because there was still bread to bake, water to fetch, animals to feed.

- “He didn’t breathe at dawn.”

“Did you warm him?”

“Yes.”

“Then wash him.”

“I will after the bread.”

To modern sensibilities, that sounds cold. But it can also be read as a different kind of endurance: grief folded into survival, because survival doesn’t pause.

Status did most of the talking.

A big thing period films flatten is hierarchy. In a lot of older societies, you didn’t need to “develop character voice” to communicate power—rank did it for you. Who speaks first, who stays silent, who asks questions, who gives orders: these are not just personality choices. They’re rules.

So instead of theatrical confrontations, you get compressed exchanges that are really about consequence:

- “You didn’t come.”

“My foot was split.”

“You should have come.”

“I couldn’t.”

“You’ll pay the fine.”

“How much?”

“Two days’ grain.”

No big speeches. No moral framing. The point is not persuasion; it’s enforcement.

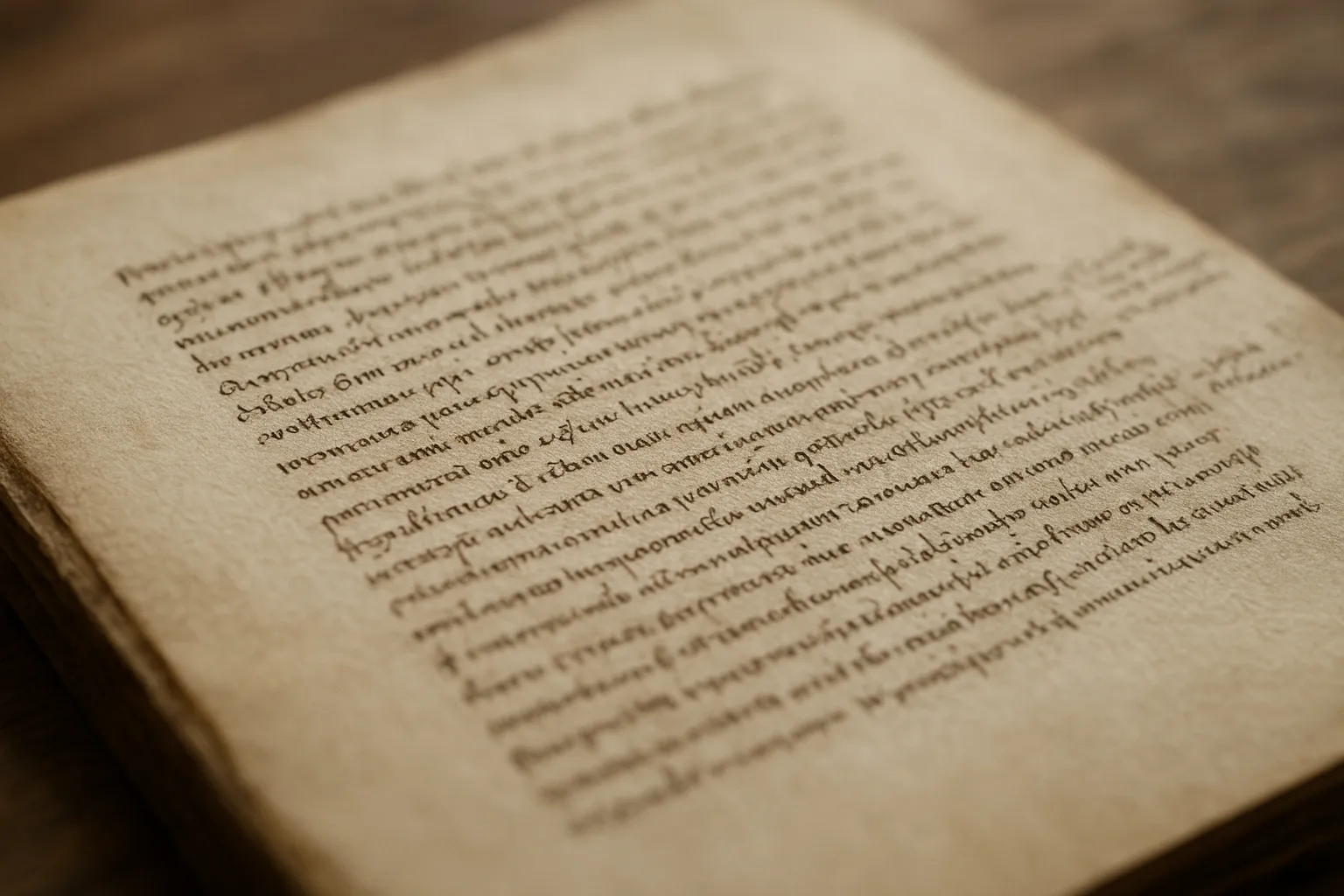

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Movies love defiance because defiance is cinematic. Real life in rigid hierarchies often runs on something less dramatic and more chilling: compliance, bargaining, and resignation.

Taverns weren’t therapy rooms. They were loud, transactional, and watchful.

There’s this modern fantasy of the tavern as a place where everyone relaxes into banter, confessions, witty stories, found-family warmth. Sometimes films basically write a 21st-century bar scene and swap in tankards.

But a more plausible “social” space—especially for common people—would still be task-oriented:

- drink

- eat

- gamble

- hire labor

- hear news

- trade insults

- measure status

- stay alert

That doesn’t mean no humor. It means humor tends to be blunt, fast, and dominance-tested rather than carefully structured like a stand-up bit.

A style of joking that fits this world looks like:

- “You drink slow.”

“You drink fast.”

“That’s why you’re poor.”

“That’s why I’m warm.”

Short. Mean-ish. No setup. No speechifying.

And “bonding” can be nothing more than synchronized attention to the same problem:

- “The barley rotted.”

“Mine too.”

“East field?”

“Yes.”

That’s socializing. Shared hardship is the glue; talk is just the thin thread tying it together.

Here’s a full tavern scene in that register—the kind of thing that feels almost anti-cinematic because nobody performs:

- “Ale.”

- “Coin.”

- “Here.”

- “Foam?”

- “Leave it.”

- “You’re wet.”

- “Road.”

- “Bad?”

- “Worse east.”

- “Always east.”

- “You owe.”

- “I paid.”

- “Not all.”

- “I will.”

- “When?”

- “After harvest.”

- “If there is one.”

And the room doesn’t need to “develop.” It just continues:

- “They came through last week.”

- “Who?”

- “Tax men.”

- “How many?”

- “Enough.”

- “Take grain?”

- “And the pig.”

Nobody says, I’m scared. They say, Hide the grain. Fear shows up as logistics.

Storytelling was richer—but it lived in a different mode than daily talk.

One mistake modern people make is assuming that because oral cultures had epics, everyday conversation must have sounded epic too. That’s like assuming because we have novels, we talk like novels.

In many societies, storytelling was a distinct register: performed, patterned, often public. It’s where beauty and symbolism lived. It wasn’t necessarily the way you asked for ale or discussed a broken bridge.

So you might get something like:

- “He crossed the forest alone.

The demon spoke sweetly.

The arrow did not waver.

The head fell.”

And then the “analysis” afterward isn’t a TED Talk about trauma. It’s still compressed:

- “Was he afraid?”

- “He went alone.”

- “Then he was.”

Meaning is inferred. Emotion is assumed. The listener does a lot of the work.

That division—plain daily speech vs heightened ritual/story speech—is one reason films feel off when they make every exchange sound like a monologue. They’re importing the epic register into the kitchen.

This is why period dialogue feels “wrong” when it gets closer to reality.

When you remove:

- constant self-explanation

- verbal reassurance

- cleverness as baseline

- emotional labeling

- individualized backstories in casual conversation

…you get something that can sound harsh or empty. But it may be closer to how speech behaves under pressure and constraint: minimal bandwidth, high stakes, low privacy, strong norms.

A lot of historical dialogue that would be “accurate” is not expressive. It’s instrumental. It points at the thing that needs doing and moves on.

A thought that falls out of this: some autistic traits might fit that world better (and some would not).

There’s a tempting conclusion here: if social life demanded less verbal performance, wouldn’t autistic people have had an easier time?

In some ways, yes—fewer expectations to emote on command, fewer requirements to do small talk, fewer social points awarded for charisma. If the local norm is bluntness, literalness, and silence, then traits we pathologize today might not register as “odd,” just “quiet” or “practical.”

But it’s not a utopia. Older societies could be brutal toward deviance, taboo-breaking, or anyone who couldn’t perform required duties. The same world that doesn’t demand charm also may not offer accommodation. The cost of being unable to work, fight, or comply could be severe. So the fit depends on the person and the role they could hold—not on a generalized “back then was easier.”

Still, it’s worth noticing how modern life moralizes communication. We don’t just use talk to coordinate—we use it as proof of goodness. Proof of empathy. Proof of belonging. That’s a very specific cultural burden, and it isn’t evenly distributed across neurotypes.

Conclusion

Period films usually don’t portray how people actually talked; they portray a modern fantasy of the past that stays emotionally legible. Everyday historical speech, in many contexts, was narrower and more functional than our current norms—less self-disclosure, more coordination, more status. The rich language did exist, but it often lived in storytelling and ritual, not in day-to-day chatter. If you listen for what’s missing—the explanations, the emotional naming, the constant “processing”—a lot of modern dialogue starts to look like its own kind of costume.