Growing Up Gifted, Then Finding the Missing Explanation

A childhood labeled “genius” masked patterns of obsession, social confusion, and misdiagnosis that didn’t fit the usual narratives. Discovering neurodivergence didn’t fix everything—but it finally made the past coherent and made self-blame unnecessary.

Posted by

Growing Up “Gifted” — and Quietly Lost

For as long as I can remember, people thought I was a genius.

For as long as I can remember, people thought I was a genius.

Not in a quiet, “oh he’s smart” way. More like that early-childhood kind of awe adults get when a kid does something that feels impossible for their age. When I was three or four, I could make every letter of the alphabet using only hand gestures. People loved it. They’d bring it up like a party trick, like proof that I was “special.”

Alongside that, I had traits that didn’t look cute—just confusing. I was grumpy. I was quieter than other kids. I didn’t seem interested in the usual toddler chaos. I also had odd eating habits that, in hindsight, were basically neon signs. I would never put random objects in my mouth. My parents didn’t have to worry about me swallowing coins or chewing on toys. That fear—apparently a common one—just didn’t exist with me.

At the same time, I was a fussy eater. If I got obsessed with one food, I’d eat it over and over and over again and reject everything else like it was poison. I was also a little spoiled—enough that people described it as “cute” instead of “a problem.” That’s important, because when something looks cute, nobody investigates it. They just smile and move on.

That was my early childhood: unusual, but packaged well enough that it didn’t trigger alarms.

School Was Easy. People Were Not.

When school started, I became the kind of child adults love. Quiet. Obedient. Not disruptive. The kind you can point to and say, “Why can’t everyone be like him?”

But I wasn’t exactly “easy.” I did everything my own way. I didn’t rebel loudly. I just… didn’t plug in the way others did.

I drew constantly. Cars, objects, anything mechanical. I could draw in 3D early, and my mother was genuinely impressed by it. By the time I was six, I could play the piano decently—not prodigy-level, but “that’s not normal for a six-year-old” decent. I could capture facial expressions in cartoons I drew, like I was studying faces as a system rather than just doodling.

Academically, I barely tried and still did fine. I wasn’t always the topper, but the marks came without a lot of effort. School felt like a predictable machine: input a little work, output good enough results.

Social life was not a machine. It was a minefield.

And what made it worse was that I didn’t even know it was a minefield. I couldn’t name what was happening. I just sensed that normal interactions had invisible rules. People would say things like:

- “Just ask.”

- “Just answer.”

- “Just be confident.”

- “Just talk.”

Those sentences landed in my head like instructions written in a language I didn’t speak. Everyone else seemed to have freedom inside conversations—freedom to ask, to joke, to take space. For me, every small interaction felt loaded with assumptions I couldn’t see.

At the time, I didn’t interpret it as a “struggle.” I interpreted it as something not worth solving. So I didn’t. I found other places to put my attention.

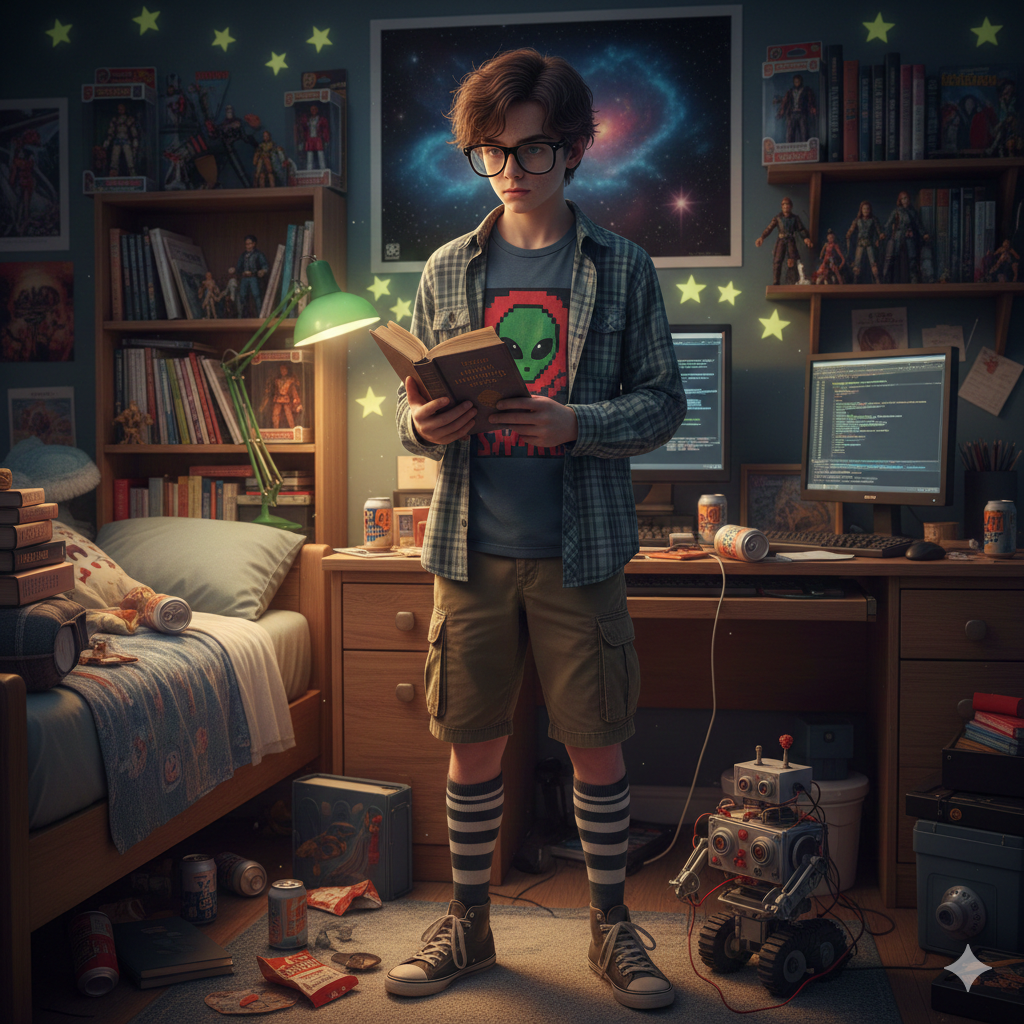

Escape Through Obsession

By the time I was around ten, that “other place” was computers.

Not casually. Not as a hobby. As an escape hatch.

I could spend absurd amounts of time on the PC. I’m talking 18 hours straight as a 12-year-old. That wasn’t “kids these days.” That was obsession. My parents eventually had to intervene, because left alone, I would’ve dissolved into the screen and never come out.

It wasn’t only games, either. My brain latched onto topics like a vice. I got obsessed with physics. Electronics. Random deep interests that didn’t match what kids around me were doing. Some of it was genuine curiosity. Some of it, if I’m being honest, was status-seeking—being the “smart kid” is a form of social currency when you don’t have the usual kind.

But the pattern was consistent: I could go deep on systems, concepts, and solitary mastery.

What I couldn’t do was pick up the “normal” scripts that adults swear are the keys to life:

- Study hard.

- Work hard.

- Be polite.

- Be friendly.

- Be available.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

None of that really connected to reality for me. I understood the words, but the translation into life wasn’t there.

When the Gap Became Obvious

As I moved into late school and early college, the importance of social skill stopped being optional.

I started noticing people around me who were naturally charismatic. People who understood grooming and clothing and posture and timing. People who knew how to walk into a room and quietly establish rank. Social hierarchies emerged, and it became obvious that “being good” wasn’t the same as being valued.

Here’s the part that I think is hard to explain to someone who doesn’t experience it this way: most people can see the link between action and outcome in social life.

They know, intuitively, that if they do X, they get Y:

- Dress well → respect.

- Speak confidently → warmth.

- Maintain networks → opportunities.

- Perform likability → protection.

For me, that cause-and-effect chain was missing. Not “weak.” Missing.

So whenever someone gave me advice, I would get stuck at the exact point where they expected magic to happen. They would say, “Talk more,” and I’d think: Talk about what? When? How much? With what facial expression? With what tone? And what happens if I misjudge it?

Everything felt like performance, and worse—like performance without a script.

By 15 or 16, I had to leave my school and move to another college. Socially, it was a wipeout. I had almost no friends. I met one or two fringe individuals like me, and those friendships lasted. But I didn’t have a “group.” I didn’t have that built-in network most people carry forward into adulthood.

Even now, I don’t have an alumni circle to lean on. No ready-made web of “people who know people.” That’s not a tragedy, but it’s a real disadvantage—and pretending otherwise is dishonest.

Misdiagnosed, Medicated, and Still Confused

Back then, none of this had a name in my life.

So the only available explanation was the one everyone uses when they can’t explain what’s wrong: depression.

I believed it. Doctors believed it. I took medication for depression. At one point there was even talk that I might have bipolar disorder, and I took medication for that too. It messed with my head in a way I still resent when I think about it. Not because mental health treatment is bad, but because throwing labels at a mystery doesn’t solve the mystery—it just adds side effects.

Ironically, the biggest “depression treatment” I ever got was something painfully simple: sleep.

I used to stay up late gaming constantly. Toward the end of engineering, when classes were lighter, it became easier to sleep on time and wake up on time. I stabilized. My mood improved. Not because I discovered enlightenment, but because my body finally had a consistent rhythm.

But socially and romantically, nothing improved.

I never had relationships. I never had a girlfriend. I wanted it badly. I craved that kind of closeness the way people crave water when they’ve been walking too long without it. And yes, I came uncomfortably close to slipping into incel thinking—not because I hated women, but because loneliness plus confusion is a dangerous chemical mix. Somehow it didn’t harden into an identity. I’m grateful for that.

I still graduated. Undergrad and postgrad. On paper, I moved forward.

In reality, I was dragging an invisible deficit no one could see.

Adult Life Didn’t Magically Fix It

Work didn’t save me. It exposed me.

I was competent. I earned money. I had enough self-esteem by then that I wasn’t a complete doormat. And yet I kept finding myself on the shorter end of social situations—especially the petty, high-school-style ones that adults pretend they outgrow but absolutely don’t.

In my first job, I helped a colleague buy a car. I sacrificed a workday for it. We drove hours. I went out of my way to be helpful. Later, she threw a party for the car purchase.

I wasn’t invited.

Not because of anything I did at that moment. But because someone else she invited told her he didn’t like me, and she decided that was enough to exclude me. Just like that—erased.

That kind of thing is uniquely destabilizing. Not only because it hurts, but because it breaks the logic you rely on to navigate life. You think: I did something kind. I showed up. I helped. That should count for something. But in some social ecosystems, it counts for nothing—or worse, it marks you as someone safe to dismiss.

I felt socially hopeless. The advice online was useless. It was either vague (“be yourself”), manipulative (“use these tricks”), or clearly written by people who didn’t have my brain. Even when I could follow the advice, it felt like acting in a play where I didn’t understand the plot.

The Missing Explanation Finally Appeared

The turning point came in a surprisingly mundane way: family.

A cousin of mine was properly diagnosed by a psychiatrist with Asperger’s. His mother—my aunt—is a psychologist, so this wasn’t vague self-diagnosis floating around in a WhatsApp group. It was real.

I started reading about Asperger’s. I didn’t do it dramatically. I did it the way I do everything: intensely. And it was unsettling how much of it matched me.

Around 2016, the idea landed: this isn’t just depression. This is neurodivergence. Back then I thought in terms of autism, because “neurodivergent” wasn’t as common in everyday language.

I asked my aunt, and she said it might be. Then she said something that hit like a missing puzzle piece clicking into place: it likely started with my grandfather—my mom’s dad. Like, this runs through the family. This isn’t a personal failure; it’s a pattern.

That didn’t make everything easy. But it made everything make sense.

Suddenly, my entire history reorganized itself:

- The early “genius” fascination.

- The obsessive interests.

- The social confusion.

- The way I couldn’t convert advice into action.

- The fact that competence wasn’t enough at work.

- The exhaustion of politics and impression management.

I wasn’t broken. I was operating with a different operating system in a world built around another one.

The Relief of Having Language

It’s been about a decade since I learned this, and I think about neurodivergence every day.

Not in a tragic way. In a clarifying way.

It’s comforting to map my experiences onto patterns that other people have already described. It gives me vocabulary for things I used to experience as raw shame. It puts feelings into frameworks. It helps me separate “I’m flawed” from “I’m different and this environment punishes that difference.”

Most importantly, it dissolves the loneliness. Not because I suddenly became social, or because the world got kinder, but because I can finally name what’s happening while it’s happening. That alone changes everything.

Conclusion

For years, I lived inside a story where I was either “gifted” or “failing,” with nothing in between. Learning I’m neurodivergent didn’t solve my life, but it gave my life a coherent explanation. And once you have an explanation, you can stop treating every struggle like a moral defect. You can start building a life that fits your brain instead of constantly punishing yourself for not fitting someone else’s script.